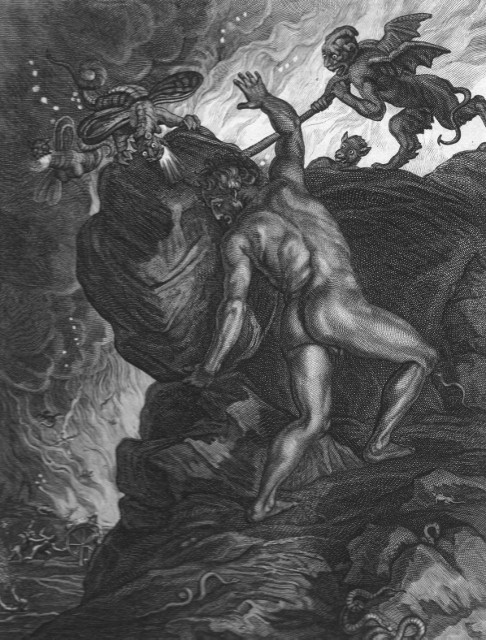

The rock has rolled downhill again. The Sisyphean slog toward rational mental healthcare once more has been flattened under the weight of judicial folly.

On Friday, November 15, the Vermont Supreme Court ruled in favor of a plaintiff suffering from years of diagnosed schizophrenia—a person [mark this word] with a history of episodic violence and aggression, and periods of catatonia—who had asked not to be medicated against his will.

The ruling means that this plaintiff has likely ingested his last medical stabilizer against psychotic episodes—the final internal barrier to hallucination, delusional thinking, disordered speech and movement; and, in rare cases, violence to themselves and/or others. (It’s also likely that he wrote his request while stabilized, an irony that I will examine later.)

According to the court decision itself, as reported in the Rutland (VT) Herald, this person’s propensity to violent and aggressive acts while in the grip of psychosis is not merely theoretical. He has committed such acts before.

The court’s wording: “Patient has a history of unpredictable violence and unprovoked aggression toward hospital and treatment facility staff, police and others.”

Given the annals of psychiatric case history, there is little reason to doubt that, when seized by psychosis in the future, he will do so again.

My own family’s experiences testify to this likelihood. Our younger son Kevin was diagnosed as schizophrenic in 2003. He rejected his antipsychotic medications in 2005, and in July of that year, a week before his 21 st birthday, Kevin hanged himself in the basement of our Middlebury home.

It’s essential to pause here and parse the meaning of “person.”

The man in question—the core person—is not inherently a criminal, just as life-affirming Kevin was not inherently suicidal. The authentic person is described as intelligent, a reader, a researcher of information. It is the incurable disease itself, which invaded the person’s brain and has rendered his life hellish since the age of 12, that bears responsibility for his aberrant impulses.

The basis for the court’s ruling seems to be an “advance directive” created and signed by the patient in 2017, in which he stated that he wanted no neuroleptics or antipsychotics, no psychiatric drugs, “no medications I do not desire at the time.” Advance directives are documents that state the signatory’s medical-care wishes in the event the writer has lost the capacity to make such decisions on his own.

I believe that the Vermont Supreme Court’s ruling in this case was misguided. I believe it poses risks to people who come in contact with the plaintiff (or more accurately, with his psychosis); risks to the plaintiff himself; and risks as a dangerous precedent, for the same general reasons.

I don’t write these words lightly. Severe mental illness is a uniquely accursed affliction that defeats good intentions and pits legitimate purposes against legitimate purposes, as in this case. No one wants to live in a society that withholds a person’s right to control her medical destiny.

But there is that stubborn word again: “person.” It’s revealing that the plaintiff wrote and signed his advance directive in 2017, a period in which he was in the care of the Brattleboro Retreat for a sixth time and was being administered the antipsychotic medication compound trifluoromethyl phenothiazine. Presumably he was in relative control of his thoughts and actions. If so, he was in (relative) control exactly because of the medication. This is the irony I promised earlier.

I write “relative” control because a frequent traveling companion of schizophrenia is anosognosia—a medical term for “lack of insight.” Anosognosia shows up in about half of all schizophrenia cases. Its effect is to convince the sufferer that everything is fine. There is no disease. And so, no need for medications and their often harsh side effects.

Ultimately, the Vermont Supreme Court decision was grounded in “rights”: the “right” of a citizen to be free from involuntary medical treatment if he so decides. But what if the decider is not the citizen but the disease itself? In my clearly non-judicial opinion, the “right” in such a case must default to the core person: the entity who will be among those harmed, perhaps fatally, by the disease’s “harm to self or others.”

Vermont, and the nation, need to drastically reconsider the balance of legitimate purposes in granting medical immunity to people who are incapable of judging that right in a rational way. The entire question of “rights” in this context is an artifact of overzealous liberal activism in the 1960’s. Vermont is a fairly liberal state, and I personally hold to liberal views. But this is not really a question of ideology. It is a question of common sense.